Paper Pursuit #5 - The Tail At Scale

Authors: Jeffrey Dean and Luiz André Barroso [2013]

Original paper: The Tail at Scale

Introduction

The Tail at Scale is an important paper in distributed systems focusing on the highly-ignored area of tail latency at scale. It is written by two Google engineers who have summarised their learnings from operating large-scale systems and how tail latency can become a considerable bottleneck.

What is tail latency?

Let’s break it down further - “tail” and “latency”. Latency is the time a system takes to serve a request. E.g. if you run an e-commerce service that returns a list of products for a brand, the time taken from the moment you make the request until you get a response is the latency value for your request.

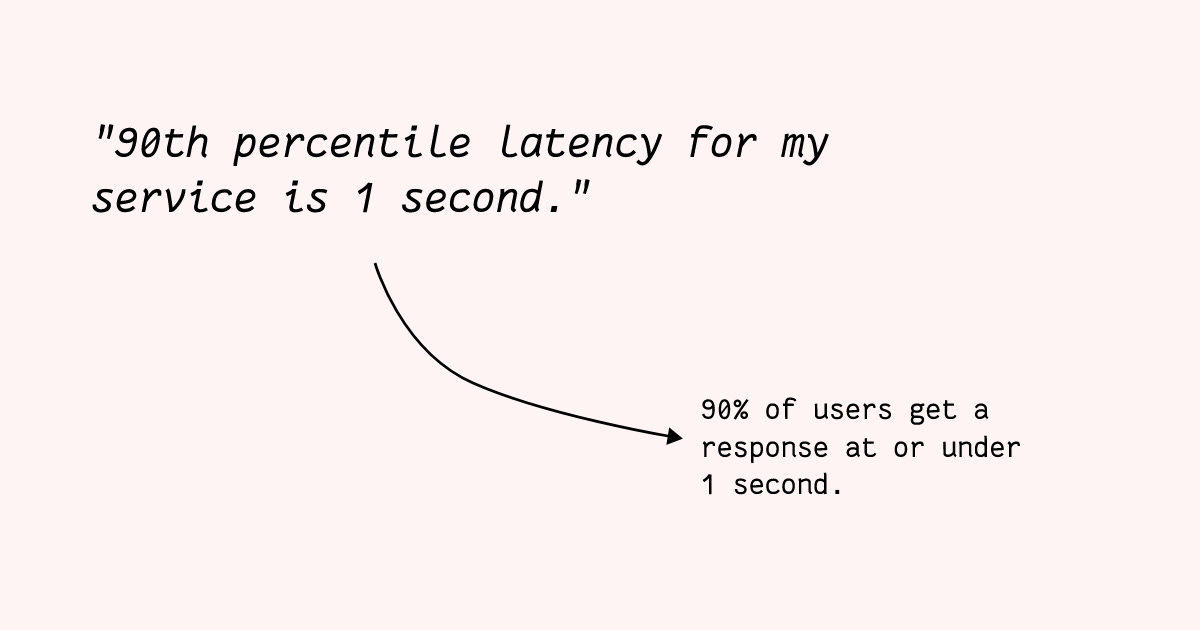

When you operate a system for more than just your friends and family, you will need a more aggregated representation of the latency than individual request latencies. A naive solution would be using mean (average), but a bit of statistics study will tell you that means are not a great way to represent latencies as some outliers can skew the average value by a large amount.

A better way to represent overall latency for a system is using percentiles. Simply put, percentiles are a way to say that “k % of values are below the stated value”, e.g. if I get a 99 percentile score on a test, it means that 99% of people who appeared on the test have a score equal to or lesser than me.

Tail latency is the 98.xxx to 99.xxx percentile latency for a system. It is the highest latency experienced by the ~1% of the users of your system. Usually, this can be ignored if you do not have a lot of users — you can assume that most of the users are happy because they are being served really fast, but things get interesting at scale.

Why does this variation exist?

The paper then discusses why such variability exists in system latency. Why does a small set of requests get served really slowly than the others? Usually, this is because of the following reasons:

Shared resources: Services may be sharing physical resources with other services and might have to compete for them.

Background processes: Scheduled background processes can cause spikes in resource usage.

Maintenance: Things like cache refresh, clean up etc. can lead to an increase in latency.

Queueing: Queueing at various levels in the system can create unpredictable variability in latency.

Garbage Collection: Regular GC cycles can affect service performance.

Power limits and energy management: CPUs can throttle performance to keep energy consumption in check.

At scale, the otherwise negligible latency variability can cause a substantial impact on the overall user experience of your system. This post by Marc Brooker visualises the tail latency as the number of servers increases, both in a parallel and a serial fashion.

“… for example, consider a system where each server typically responds in 10ms but with a 99th-percentile latency of one second. If a user request is handled on just one such server, one user request in 100 will be slow (one second) … if a user request must collect responses from 100 such servers in parallel, then 63% of user requests will take more than one second”

The example above from the paper shows how tail latency can bite us at scale. I have included the math (which I struggled with in the beginning) as a footnote1.

Tail-Tolerant Systems

Instead of trying to avoid these tail latencies, the paper suggests thinking in terms of tolerance. Latency variability will always exists, we need to make systems tolerant of this variability. There are two ways to approach the problem — a within-request method which operates to resolve the variability in the short term, and a cross-request method which tries to solve it over a longer period of time.

Within-request methods

The following methods can be applied at a request level to curb high latencies.

Hedged Requests

Request hedging is to simultaneously send a request to a set of server replicas and use the response from the replica that responds first. All other requests are cancelled. This is a great technique to reduce the probability of slow requests as we take the “best of all” approach.Though this sounds great at first, it can lead to unnecessary load on all replicas. A solution to this is to make these requests with small time delays in between. A second request is only sent if the first one takes longer than the 95th percentile of the latency expected for the type of request.

Tied Requests

Hedged requests provide a considerable benefit but may cause multiple servers to process the request which may never be used. The latency of a request is substantially predictable once a server picks it from the request queue — queueing is the biggest source of variability.

Tied requests are a set of requests that are sent out to replica servers similar to hedged ones, but they are also able to communicate with each other and are able to dequeue/cancel others if one of them is picked up for processing.

Other alternatives:

Probing servers before sending the request to the least loaded server.

A server only forwards requests to replicas if it does not have a cached response. The forwarded requests are cancellable with cross-server messaging.

These techniques help reduce the impact of tail latencies considerably on a request level. The paper then moves to discuss more coarser-grained solutions that can be applied over a longer period of time in a system.

Cross-request methods

These techniques can be applied at a more higher level e.g. at the service level latency or to manage unbalanced load across replicas. When partitioning data, assigning data partitions to underlying machines in a one-to-one fashion does not scale well. This is because the performance of machines is unreliable and non-uniform over time and because the load on a partition may vary depending on certain items that become popular.

Decoupling data partitions from machines allows us to easily move the partitions around among machines and load balance effectively.

Micro-partitions

To avoid the coupling of partitions and machines, many Google systems use micro-partitioning, i.e. there are many more partitions generated than available machines and these partitions are then dynamically assigned to machines and load balanced.

Selective replication

Extending the micro-partitioning concept, one can predict/detect which data items will lead to a load imbalance and create additional replicas of these items. These replicas can then be copied over to multiple micro-partitions and load-balanced to avoid unbalanced load on a single partition.

This is used in Google’s Web Search system where documents that are becoming popular (attracting high search queries) are copied over to multiple micro-partitions to reduce overall latency and load imbalance.

Latency-induced probation

This is a fail-fast method where a system detects and decides to suspend a particularly slow-behaving machine and allows it to recover. It keeps sending it shadow requests to check if it has recovered to resume the normal flow. The slowness is usually a temporary phenomenon that is expected to subside when the load on the machine is reduced, giving it an opportunity to recover.

Large Information Retrieval Systems

For systems responsible for retrieving information from a large data set, there are some specific techniques to ensure low latency.

“Good enough” approach

Such systems should try to return good enough results quickly than waiting to return the best results. The probability of finding the best result further down the data graph (in the case of a search system) is very low, hence it is profitable to return the results that have been found.Canary requests

Usually, such systems involve fanning out a request to multiple leaf servers in parallel and then aggregating the collected data. Such fanning out may result in the request taking untested code paths that may lead to crashes or high latency. To avoid this, Google systems send the requests to a small number (one or two) of leaf servers first, and if these respond successfully only then the request is made to the remaining leaf servers.

Mutations are generally easier than queries w.r.t. latency variability. This is because they can usually be done asynchronously and the systems updating state (e.g. databases) can implement various algorithms to ensure high consistency.

Takeaways and further readings

The paper states that with the increasing hardware heterogeneity (circa 2013), software techniques to curb latency variability will become more important over time. It introduces the key idea of “tail-tolerant” which suggests not trying to remove latency variability altogether but rather devising techniques considering it will always be present.

This is very similar to fault-tolerant systems, as I have discussed in an earlier issue, where we assume that systems will fail. The techniques suggested in the paper add minimal overhead and provide considerable benefits for latency variability. Today, these can easily be implemented using libraries or frameworks.

Did you learn something new in this issue? Share it with someone you know who might also find this interesting! I’ll see you again next Tuesday. 💛

If a server has a 99th percentile latency of 1 second, with 1 server the system responds to 1% of the user requests slowly (i.e. in 1 second). If there are 100 servers, the probability of a slow response increases as we take the product of all probabilities.

Since the latency of each server is independent, the probability of encountering a latency outlier among the 100 servers is given by the complementary probability of all servers responding within 10ms.

P(all servers responding within 10ms) = 0.99 ^ 100 ≈ 0.37 = 37%

P(a user request taking more than 1 seconds) = 1 - 0.37 = 0.63 = 63%

Thanks!